March 26, 2023 - PBS News Weekend full episode

3/26/2023 | 26m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

March 26, 2023 - PBS News Weekend full episode

Sunday on PBS News Weekend, we look at growing health concerns about “forever chemicals” and what can be done to avoid them. Then, why there are so few Black male teachers in American classrooms. A new documentary is raising awareness about endometriosis, a debilitating disease that is difficult to diagnose. Plus, the story of a Native photographer who captured images of her own community.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Major corporate funding for the PBS News Hour is provided by BDO, BNSF, Consumer Cellular, American Cruise Lines, and Raymond James. Funding for the PBS NewsHour Weekend is provided by...

March 26, 2023 - PBS News Weekend full episode

3/26/2023 | 26m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Sunday on PBS News Weekend, we look at growing health concerns about “forever chemicals” and what can be done to avoid them. Then, why there are so few Black male teachers in American classrooms. A new documentary is raising awareness about endometriosis, a debilitating disease that is difficult to diagnose. Plus, the story of a Native photographer who captured images of her own community.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch PBS News Hour

PBS News Hour is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipJOHN YANG: Tonight on "PBS News Weekend," the growing health concerns about so called forever chemicals and what can be done to avoid them.

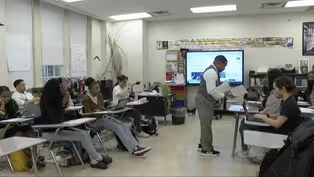

Then, as teacher shortages hit schools across the country, we look at why there are so few black men leading classrooms.

And a new documentary raising awareness of endometriosis, the often debilitating disease that's difficult to diagnose.

WOMAN: This is a human issue.

Every single viewer watching this right now is affected by endometriosis.

(BREAK) JOHN YANG: Good evening.

I'm John Yang.

It was another day of unsettled weather in the Southeast, even as residents and rescue teams in Mississippi comb through what's left of flattened homes and buildings.

President Biden declared a major disaster across the stretch of the Mississippi Delta that was ravaged by a deadly tornado late Friday that adds federal funds to the rebuilding effort.

At least 25 people were killed in Mississippi.

Dozens more were injured and hundreds displaced as the storm ripped through several towns.

Overnight, in Georgia, storms destroyed entire city blocks.

Severe thunderstorm watches are still in effect in parts of the region.

Former President Trump gave his first public remarks about a possible indictment in a New York case centering on hush money payments to several women.

At his first 2024 campaign rally last night in Waco, Texas, Mr. Trump said it's all just politics.

DONALD TRUMP, Former U.S. President: The new weapon being used by out of control unhinged Democrats to cheat on election is criminally investigating a candidate.

They couldn't get it done in Washington, so they said, let's use local offices.

JOHN YANG: The Manhattan grand jury hearing Trump's case is expected to reconvene this week.

If indicted, Mr. Trump would be the first former president ever to be charged with a crime.

A fourth person has died as the result of an explosion on Friday that leveled a chocolate factory outside Philadelphia.

Three people are still missing.

A weather camera in West Redding captured the blast at the RM.

Palmer plant.

Investigators are still trying to determine the cause.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu fired Defense Minister Yoav Gallant today, one day after Gallant called on Netanyahu to delay his contentious plan to overhaul the justice system.

The plan has set off mass protests, unrest in the military, and now cracks in the fragile governing coalition.

Following today's announcement, protesters return to the streets, including near Netanyahu's own home in Jerusalem.

The Israeli parliament is preparing for a vote on the proposal early next week.

President Biden is looking for a new person to lead the Federal Aviation Administration.

His previous nominee, Philip Washington, has withdrawn from consideration after critics questioned his qualifications.

He's currently head of Denver's Airport.

The FAA hasn't had a Senate confirmed administrator for nearly a year now, as commercial aviation has been plagued with close calls, it malfunctions and delays in cancellations.

Still to come on PBS News Weekend why are there so few blackmail teachers in American classrooms?

And the story of a Native American photographer who captured images of her own community.

(BREAK) JOHN YANG: There's a class of toxic chemicals so pervasive that they're found in food, soil, water and in the blood of most people in America.

Earlier this month, the EPA proposed the first ever regulatory standard to limit the quantity allowed in drinking water.

Ali Rogin looks at the growing health concerns about these chemicals.

ALI ROGIN: PFAS, sometimes called forever chemicals, repel fire, water, oil and stains and have been used since the 1940s in a wide variety of everyday products.

You can find them in nonstick cookware, fast food wrappers, clothes, and cosmetics.

But these manmade chemicals don't break down easily, and a number of them have been linked to serious health problems.

For more on their impact, we turn to Erin Bell.

She's an environmental epidemiologist at the State University of New York at Albany who studies human exposure to these toxins.

Erin, thank you so much for joining us.

Just how widespread are these chemicals?

ERIN BELL, Environmental Epidemiologist: These chemicals have been detected in the drinking water and soil in every state of the United States, and it is also being detected in many countries across the world.

A number of health concerns are related to exposure to these chemicals.

They include impact on the immune system.

Folks with higher exposures are more likely to have thyroid changes in kidney function as well as higher cholesterol.

We're also concerned about impacts on children with regards to low birth weight and neurodevelopment in those children.

There are a number of other health outcomes where the literature is more mixed.

We sometimes see an association, other times we see less of an association, and we have more work to do.

These would include infertility factors around ulcerative colitis and other autoimmune diseases.

ALI ROGIN: Are these things that people can determine by taking a blood test?

I mean, how does one test to see where their levels are?

ERIN BELL: That's correct.

For each individual, we measure concentrations in their blood, and that is the best way to determine the individual level of exposure for people who have lived in communities or for people in occupations that have these higher exposures.

Unfortunately, there's no consistent guidance or coverage from insurance companies for testing for PFAS in your blood.

If you contact your local health department, they will let you know if there are programs at the state level sponsored through state health departments if they have opportunities for you to get tested.

This is a situation that we're still working on in terms of making sure there's coverage for people to get tested if they wish to know what their levels are.

ALI ROGIN: Now, the EPA, as we mentioned in the introduction, is proposing a new regulation pertaining to PFAS in water.

Can you explain what exactly this proposal would do?

ERIN BELL: There are 12,000 chemicals in the family of PFAS.

The EPA has suggested that for six of these chemicals, there be a standard federal rule that would require that water utilities test for these six chemicals and if they were above a certain level that those chemicals would be monitored for and regulated and companies would be required to reduce their exposure in the water utility.

ALI ROGIN: Now, six out of 12,000 doesn't sound like a lot.

Are we missing something here?

Are these very significant versions of these chemicals?

ERIN BELL: So that's an excellent question and this is one of the challenges we have in the field.

Out of the 12,000 we've obviously studied very few of them.

So these six are particularly concerned because we know the most about them.

We also have detected them in higher levels in drinking water across the country.

However, it is quite literally a drop in the bucket.

It is just a very small number.

There is concern in the scientific community that we will never catch up in terms of understanding what the health effects are for the much larger group of PFAS.

ALI ROGIN: How is it that these companies are able to continue to manufacture products with these dangerous chemicals in them?

ERIN BELL: So historically, when we talk about environmental exposures and removing them from production, we focus on their persistence.

They stay in the environment and in our bodies for a very long time.

The newer versions, they are not as long lasting in the environment.

However, because they are structurally designed to, in essence, do the same thing that made them good for production and for our consumer products, they're still related to some of these adverse health outcomes.

So, they're still being used because we have not regulated them and we still require them in the manufacturing process.

And until those rules and laws change, then that will be allowed to happen.

ALI ROGIN: So my understanding is that this EPA rule, if it is approved, is still going to take a few years before it's fully operational.

What kind of things can people do if they want to begin reducing their exposure now?

ERIN BELL: There are a number of things that people can do and communities can do.

The first is awareness.

Please be sure and keep mindful of what might be going on in your community, especially in the drinking water.

If you are not sure what levels of PFAS are in your drinking water, you can contact your local water utility, your state health department, as well as any university or college researchers that are in the area.

In terms of reduction, we can use filters on our water systems and in our homes.

You also want to be mindful of what you use on an individual basis, again, minimizing fast food wrappers.

The wrappers are lined with these materials, as well as microwave popcorn is another example.

Pots and pans have these linings.

As they become scratched, the PFAS can leach into the food and cause us more exposure.

So again, be mindful of that and as you replace them with things that don't have the nonstick chemicals or have the other types of coatings on them that would potentially have these chemicals.

ALI ROGIN: Erin Bell with SUNY Albany.

Thank you so much for your time.

ERIN BELL: Thank you.

JOHN YANG: This past week, employees from Los Angeles schools went on strike, demanding, among other things, staffing increases.

But teacher shortages are an issue beyond LA.

More than half of public schools report being understaffed, and bringing diversity into the classroom is a big part of that.

In the 2020-2021 school year, fewer than 2 percent of teachers were black men, while 61 percent were white women.

Earlier, I spoke with Mark Joseph of Call Me Mister, a program that aims to recruit and retain diverse students pursuing careers in education.

I asked him why there are so few black male teachers today.

MARK JOSEPH, Program Coordinator, Call Me Mister: I think part of it is there's a huge disconnect with many African American male students in terms of their fit in today's classrooms.

Many of them are in those spaces day in and day out.

They don't feel seen, they don't feel connected.

They just don't understand their role and heir place or really how school plays a significant impact in their lives moving forward.

And so that's why what we have been able to do as a program is to take those same experiences that they've had during that K 12 journey and address those things in a kind of way to where, we can emphasize leadership, we can emphasize relationships, and we can emphasize development in terms of being.

able to go back to serve in those spaces that you didn't see yourself leading at one point in time.

JOHN YANG: How much of this is a vicious cycle?

You talk about young black students not feeling seen, not feeling involved.

How much would it help to have teachers who look like them at the head of the classroom?

MARK JOSEPH: Yes, I think it's extremely important and we all know and understand.

There's no magic potion that we could take, and there's no magic pill.

The reality is that those same African American males that everyone says they're looking for, we know and understand that they sit in our classrooms day in and day out.

However, the reality is, how do we tap into their potential so that these same individuals can then return into those classroom spaces, leading those classrooms, instructing those classrooms, really connecting to students in a way that only they could do it.

JOHN YANG: Lately, we've been seeing the public schools become the battleground for the culture wars.

Do you think that might lead or discourage some black men from going back as teachers?

MARK JOSEPH: I believe so.

You know, education as we now know it and understand has really taken a significant hit in the public's eye.

And so the natural understanding is, why would I want to go into that space?

If all I'm hearing about education and being a teacher is so negative.

Why would I find myself in that particular position?

One of the things that we try to do and live by, how do we change the narrative of what it means to be an educator in this day and age?

Because truthfully, we realize the challenges.

We realize the hardships that may encounter being an educator.

But the truth of the matter is, what generation didn't encounter some level of challenge and cause of the commitment of the previous generation it has given us an opportunity to do what we're passionate about today.

It has given us an opportunity to serve our communities, our schools, and most importantly, our young people in a way that it will benefit them to be able to move forward in our society.

JOHN YANG: Tell me specifically what is Call Me Mister doing to try to achieve all these goals?

MARK JOSEPH: Our program is designed to address retention, recruitment and development.

And so when we look at it on the recruitment end, we know that we can't just recruit individuals into the profession the same old way that we've done many years before.

We've learned how to leverage and use our stories and the stories of many of the educators that have gone through this program to really connect to the students that we try to recruit.

The retention piece is so critical as well because it makes no sense to bring individuals into the program and you can't retain them.

It's an opportunity and an experience where young African American males get an opportunity to work together.

They get to go to classes together.

They get to study together.

You get to do it with a cohort of individuals, with that same fire, with that same passion and with that same love of being an educator and serving our young people.

And then the last component the developmental stages.

We do know and understand that in order to become that effective teacher, we have to put our individuals through a developmental process.

And all students deserve an effective educator.

An educator that's willing to see them and an educator that's willing to move them forward.

An educator that's willing to create new experiences and opportunities, not just for one type of students, but all students in that classroom environment.

That's the mission of our program to recruit, to retain, and to develop and to place these individuals into our classrooms today.

JOHN YANG: Mark Joseph of Call Me Mister.

Thank you very much.

MARK JOSEPH: Thank you.

JOHN YANG: Endometriosis is a disease that affects one in 10 people with uteruses over the course of their lifetime.

It occurs when tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows somewhere else in the body, typically on or around reproductive organs.

It can cause debilitating pain and often leads to infertility.

But after symptoms begin, it can take years for doctors to correctly diagnose it.

A new documentary tells the story of several people as they battle endometriosis and fight for more awareness of the disease and for treatment for it.

WOMAN #1: I knew something was weird.

I knew something was wrong.

WOMAN #2: It took me ten doctors to find someone that believed my pain.

WOMAN #3: I thought maybe I'm dying or I have some kind of rare disease.

I go online and find that millions of women are going through exactly what I'm going through.

JOHN YANG: Ali Rogin is back with a conversation with the director of that documentary, Shannon Cohn.

It's part of our continuing coverage of inequities in women's health unequal treatment.

ALI ROGIN: Shannon Cohn, thank you so much for joining us.

Many people may have heard the word endometriosis.

Maybe they know about it.

There is so much that is unknown about this disease.

What are some of the really important things that people should know about it yet?

SHANNON COHN, Director, "Below The Belt": Arguably, endometriosis is the most common, devastating disease that most people have never heard of.

It affects about 200 million people on the planet, yet takes an average of eight doctors and 10 years to diagnose it's the cause of up to 50 percent of infertility in women and puts a burden on society in the U.S. of an estimated $116 billion each year in lost wages, lost productivity, and associated medical costs.

Yet a lot of people have never heard of it.

ALI ROGIN: And in your work, what have you discovered about why it's so widespread and yet so poorly understood?

SHANNON COHN: I mean, where do I start?

There are a lot of things like endometriosis is a perfect, awful storm of so many things that apply across the healthcare spectrum.

Things like menstrual taboos and societal stigma around below the belt.

Women's issues, health issues, gender bias in medicine, racial bias in medicine, financial hurdles to care, and other institutional hurdles to care that we all go through.

All of these things combine together that make it really difficult for even this huge population of people to get the care, first of all, to get diagnosed early, and then to get the care that they need early.

ALI ROGIN: And speaking of that care, there really aren't that many options.

There's a couple of surgeries that are available.

They're extremely radical in some cases.

Often insurance doesn't cover them.

How is it that there are so few options for treatment and even those options can be hard for women to access?

SHANNON COHN: The reason why is mainly because research funding hasn't been there, enough attention hasn't been put on the disease and women's health in general to find the answers that we need to develop treatments that actually work.

A lot of the medications out there that, by the way, only treat symptoms, none of them actually treat the disease, have been around for 30 years.

They've just been repurposed.

And then another issue is that the vast for in the U.S. for example, the vast majority of the 60,000 OB/GYNs in the country, they don't have the skills to perform advanced endometriosis surgery.

If you envision an iceberg and an iceberg is a tumor or the endometriosis in someone's body, do you want someone to go in and kind of laser the top of it or do you want them to actually cut it out because you may not be able to see the whole lesion?

The issue is that the vast majority of the OB/GYNs in the country only know how to burn the top.

They just haven't had that extra skill set.

ALI ROGIN: So let's talk about what it takes to expand the breadth of knowledge, the professionals that do this.

Congress's role in the film, you highlight a family who has made it their mission to lobby the Hill, meet with lawmakers, try to get attention, and federal dollars.

What is Congress doing?

Are they doing enough?

SHANNON COHN: Well, we're definitely getting started in a really robust and meaningful way.

For several years now, we've been working with Senator Elizabeth Warren, and we started working with Senator Orrin Hatch in 2017 because his granddaughter, Emily Hatch, who appears in the film, and her mother, Mary Alice Hatch, had been phenomenal advocates, along with the late Senator Hatch in really pushing endometriosis forward in a meaningful way.

And when Senator Hatch retired in 2019, senator Mitt Romney stepped in his shoes and really pushed it forward alongside with Senator Warren.

ALI ROGIN: You had a screening on Capitol Hill.

Lawmakers were present.

What was the reaction?

SHANNON COHN: It was so wonderful to see lawmakers from both sides of the aisle come together on an issue, especially in today's political climate, to do with women's health and to see them say, what?

It's not a political issue.

This is a human issue.

Every single viewer watching this right now is affected by endometriosis.

Every single one.

Either they have it or they know or love someone who has it.

It's a guaranteed fact.

So, even if you think, oh, what is this weird word?

I don't think I've ever heard of this.

Should I care about this?

You should.

Everyone should.

Because it affects you.

ALI ROGIN: This is the second documentary that you've done on endometriosis.

Why is this form of storytelling such a powerful way to tell these stories?

SHANNON COHN: I think it's the way we affect change in the 21st century.

I always said this old adage, if you can change hearts and minds, you can change policy.

It's true.

We're all human.

You know, we all have hopes and dreams and loves and disappointments.

When you share a human story, even about an issue you're not familiar with, we all, you know, identify with that.

We identify with that common humanity.

And then, by extension, you start caring about the issues that these subjects in the film go through.

That's how we create change, because all of a sudden, you create a worldwide community saying, hey, we need to do something about this.

This isn't fair.

So that's the power of storytelling.

ALI ROGIN: The documentary is "Below The Belt", premiering on PBS.

Shannon Cohn, thank you so much for your time.

SHANNON COHN: Thank you.

It's an honor.

JOHN YANG: And for the last week of Women's History Month, we spotlight another figure whose contributions have often gone unseen.

Tonight, the first known female Native American photographer who captured personal images of her community.

Jennie Ross Cobb's, candid depictions of members of the Cherokee Nation, rarely seen by the rest of the country, cemented her place in tribal and photographic history.

The daughter of prominent Cherokee leaders, she was given a box camera in the 1890s when she was a teen and used it to capture images of her friends and family over a period of about ten years.

Her fellow students at the Cherokee National Female Seminary, friends eating snacks, playing on train tracks and her students in front of one of the Cherokee schoolhouses where she taught for several years.

They tell the story of the community the Cherokee had built after they were forced to leave their ancestral homelands in the East and of a life under threat yet again as the federal government worked to break up communally held lands to make way for railroads and non-Indian settlement.

Later in life, Cobb fought to preserve a piece of her people's heritage, campaigning to save the historic Hunter's home.

When the state of Oklahoma took it over in 1945, she became curator and restored it using her own glass plate negatives.

She remained in that position until her death in 1959 at the age of 77.

And that is "PBS News Weekend" for this Sunday.

I'm John Yang.

For all of my colleagues, thanks for joining us.

Have a good week.

Documentary shows uphill battle for endometriosis treatment

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 3/26/2023 | 6m 48s | ‘Below the Belt’ highlights uphill battle for endometriosis treatment (6m 48s)

The life and legacy of Native photographer Jennie Ross Cobb

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 3/26/2023 | 1m 30s | The life and legacy of Native photographer Jennie Ross Cobb (1m 30s)

What toxic ‘forever chemicals’ are and how to avoid them

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 3/26/2023 | 6m 21s | What we know about toxic ‘forever chemicals’ and how to reduce our exposure (6m 21s)

Why so few Black men teach in American classrooms

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 3/26/2023 | 5m 52s | Why so few Black men teach in American classrooms (5m 52s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Major corporate funding for the PBS News Hour is provided by BDO, BNSF, Consumer Cellular, American Cruise Lines, and Raymond James. Funding for the PBS NewsHour Weekend is provided by...